If the letters are in different rows and columns, replace the pair with the letters on the same row respectively but at the other pair of corners of the rectangle defined by the original pair.Locate the letters in the key square, (the examples given are using the key square above).The algorithm now works on each of the letter pairs.Break the plaintext into pairs of letters, e.g.If the plaintext has an odd number of characters, append an 'x' to the end to make it even.Identify any double letters in the plaintext and replace the second occurence with an 'x' e.g.Remove any punctuation or characters that are not present in the key square (this may mean spelling out numbers, punctuation etc.).

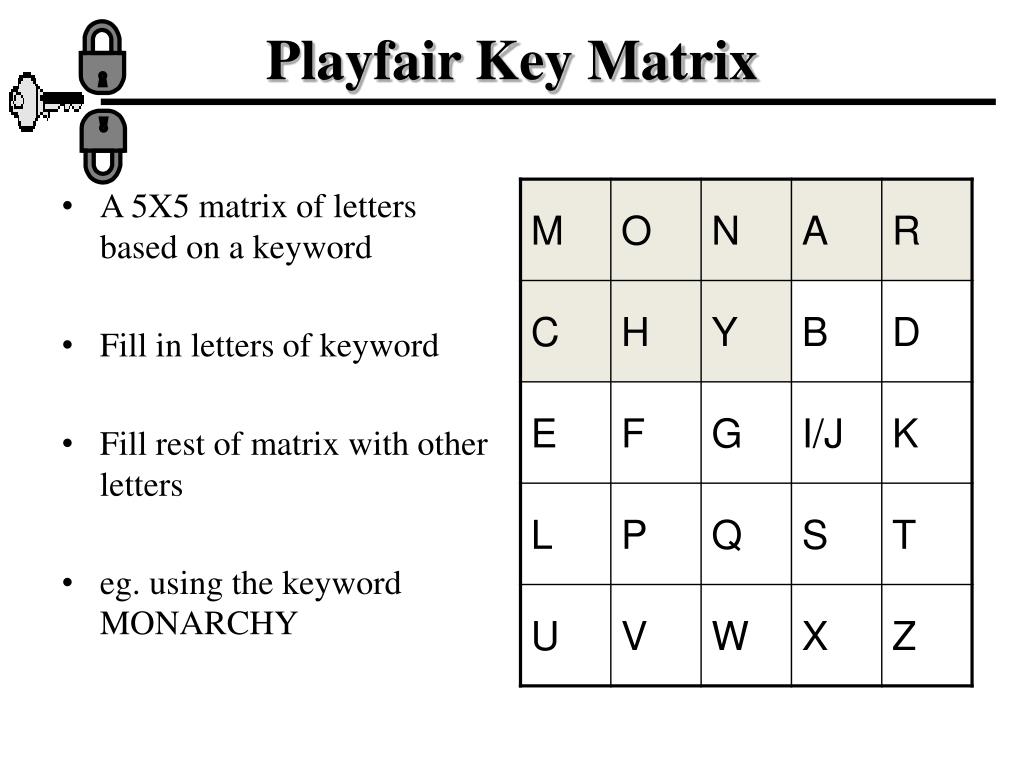

We now apply the encryption rules to encrypt the plaintext. Note that there is no 'j', it is combined with 'i'. This is then used to generate a 'key square', e.g.Īny sequence of 25 letters can be used as a key, so long as all letters are in it and there are no repeats. The 'key' for a playfair cipher is generally a word, for the sake of example we will choose 'monarchy'. Note the ciphertext above has some errors in it, see this comment for a more correct version. Evans deciphered it with the key ROYAL NEW ZEALAND NAVY and learned of Kennedy's fate. The coastwatchers regularly used the Playfair system. STRAIT TWO MILES SW MERESU COVE X CREW OF TWELVE PT BOAT ONE OWE NINE LOST IN ACTION IN BLACKETT Evans received the following message at 0930 on the morning of the 2 of August 1943: He did not know that the Japanese destroyer Amagiri had rammed and sliced in half an American patrol boat PT-109, under the command of Lieutenant John F. On 2 August 1943, Australian Coastwatcher Lieutenant Arthur Reginald Evans of the Royal Australian Naval Volunteer Reserve saw a pinpoint of flame on the dark waters of Blackett Strait from his jungle ridge on Kolombangara Island, one of the Solomons. Perhaps the most famous cipher of 1943 involved the future president of the U.S., J. By the time the enemy cryptanalysts could break the message the information was useless to them. A typical scenario for Playfair use would be to protect important but non-critical secrets during actual combat. This was because Playfair is reasonably fast to use and requires no special equipment. It was used for tactical purposes by British forces in the Second Boer War and in World War I and for the same purpose by the Australians during World War II. For a tutorial on breaking Playfair with a simulated annealing algorithm, see Cryptanalysis of the Playfair Cipher. Frequency analysis thus requires much more ciphertext in order to work. Frequency analysis can still be undertaken, but on the 25*25=625 possible digraphs rather than the 25 possible monographs. The Playfair is significantly harder to break since the frequency analysis used for simple substitution ciphers does not work with it. The technique encrypts pairs of letters (digraphs), instead of single letters as in the simple substitution cipher. The scheme was invented in 1854 by Charles Wheatstone, but was named after Lord Playfair who promoted the use of the cipher. The Playfair cipher was the first practical digraph substitution cipher.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)